A prep school student is mercilessly bullied by classmates who suspect he’s gay — to the point where he tries to commit suicide. Sounds like the kind of horror story that’s all too common in the cyber age, but in fact we’re talking about Vincent Minnelli’s 1956 film version of Robert Anderson’s play “Tea and Sympathy,” one of four mid-career Minnellis among the ambitious recent offerings by the manufacture-on-demand Warner Archive Collection. Many people who have seen neither the movie nor the play know their most famous line — “Years from now when you talk about this – and you will – be kind.” In the 2009 box-office disaster “Land of the Lost,” Will Ferrell’s character, who has just been excreted from a dinosaur, says “When you talk about this, and you will, please be gentle.”

A prep school student is mercilessly bullied by classmates who suspect he’s gay — to the point where he tries to commit suicide. Sounds like the kind of horror story that’s all too common in the cyber age, but in fact we’re talking about Vincent Minnelli’s 1956 film version of Robert Anderson’s play “Tea and Sympathy,” one of four mid-career Minnellis among the ambitious recent offerings by the manufacture-on-demand Warner Archive Collection. Many people who have seen neither the movie nor the play know their most famous line — “Years from now when you talk about this – and you will – be kind.” In the 2009 box-office disaster “Land of the Lost,” Will Ferrell’s character, who has just been excreted from a dinosaur, says “When you talk about this, and you will, please be gentle.”

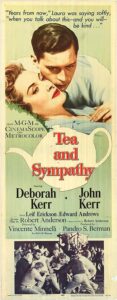

The orginal line is delivered by a ravishingly beautiful Deborah Kerr as the headmaster’s sympathetic wife, who sleeps (off-screen) with the taunted student (played by the unrelated John Kerr) to reassure him of his masculinity (among other reasons). Though dated in its theatricality (the Kerrs, and Leif Erickson, as her macho husband, are re-creating their roles from the Broadway production directed by Elia Kazan), “Tea and Sympathy” is fascinating as a contemplation on men, the expression of their sexual identities and their relationships to other men and to women by the great stylist Vincent Minnelli, who by most accounts tended toward effeminacy though his actual sexual proclivities are still hotly debated among some film historians (he was married four times, most famously to Judy Garland).

In the case of Deborah Kerr’s character, she’s clearly attracted to the folk-singing, sensitive student because he reminds her of her first husband — who died as a teenager in World War II trying to prove his own manhood. He also provides an alternative to her current husband, who clearly has a softer side but has great difficulty expressing it in the homophobic ’50s. A scene where he brings Kerr home a poetry book and discovers the boy has already given it to her is quite telling — Erickson, who in real life had been married to the famously troubled actress Francis Farmer when he was a male starlet at Paramount in the late ’30s, obviously knew from unhappy marriages.

John Kerr has some great scenes with his character’s father, played by Edward Andrews, a portly middle-aged character actor who beautifully conveys the anxiety his character is suffering over concerns his son might be what was then often called a sissy, or as he puts it in the movie code of the time, isn’t a “regular fellow.” It’s pretty clear that Andrews, who is divorced from Kerr’s long-absent mother, is worried about what people will think about his own sexuality — particularly when he discovers his son is referred to as “sister boy” and discovers a dress in his closet, a costume for the son’s female role in “School for Scandal.” Note that Minnelli practically presents Andrews and Erickson as a pair of gossipy middle-aged queens in a scene where they’re discussing the “problem” in the flower-filled backyard — much to the disgust of Deborah Kerr, who closes the window through which we’re hearing their anguished conversation.

And then there’s John Kerr’s roommate and sometimes protector, a jock played by Darryl Hickman (the Polio victim drowned by Gene Tierney in “Leave Her to Heaven”). There’s an annual bonfire event where upperclassmen try to relieve freshmen of their pajamas — which Minnelli shoots almost as if it were a Ku Klux Klan rally — where Hickman rips off the terrified Hickman’s bedclothes so he won’t have to suffer this ritual violation at the hand of a stranger.

Hickman’s own (unseen) father orders him out of Kerr’s room. But partly out of guilt, Hickman agrees to coach Kerr (whose movements are not at all effeminate) how to walk in a more “manly” manner. It’s hard to imagine the filmmakers behind “La Cage Au Folles” weren’t aware of this scene, when they included a similar sequence in their own movie. The scene was excerpted for its camp value in the documentary “The Celluloid Closet.” But in the context of the movie, it’s not campy at all — both characters are suffering anxiety about how the world might perceive their sexuality and friendship.

It may seem mild today, but “Tea and Sympathy” was a bold choice for screen material in an era when the Production Code prohibited any direct reference to homosexuality and where adultery had to be punished Robert Anderson, who adaptated his own play, was forced to add a ten-years-later framing story (most of the action ostensibly takes place in 1946) that makes it clear the dalliance has ruined Deborah Kerr’s marriage. And, perhaps less convincingly, that John Kerr is a married man with a family.

Read the rest of this post at http://nyp.st/dEkGHB