By Armond White

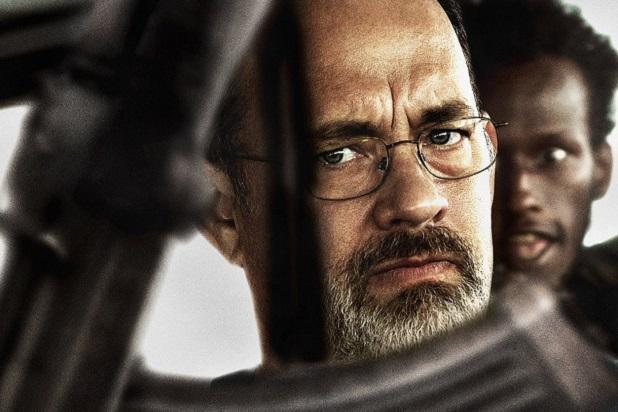

Paul (shaky-cam) Greengrass makes another mess of recent political history in Captain Phillips. This time Greengrass fakes a docu-drama about the 2009 incident when the Maersk Alabama cargo ship, piloted by Vermont merchant marine captain Richard Phillips, was seized off Africa’s eastern coast by Somali pirates, then rescued by the U.S. Navy. As in United 93, Greengrass’s 9/11 disaster-movie, Captain Phillips trivializes political crisis as entertainment. United 93 flopped because it had no star appeal, so Greengrass casts Tom Hanks to ensure audience identification–but for whom?

The kidnapping and hostage scenario depends on a fundamental hero/villain contrast that also, unfortunately, becomes a racial contrast: White American Hanks vs. virtually anonymous Black African interlopers. There’s no getting around this even though the silly script by Billy Ray glosses global economy sentiments (about the Haves inevitably endangered/targeted by the Have Nots). The film’s ridiculous suggestion that American capitalism invites hostile aggression was also implicit in United 93 and explains its fatal inability to rise above mawkishness. Greengrass’s questionable political principles (he also directed the heinous anti-American thrillers Bourne Ultimatum and Green Zone) leads to the duplicitous dramatic conceit of making the Somali pirates scary yet keeping their motives vague–and stereotypical. Few critics ever notice racism in such generic form.

The kidnapping and hostage scenario depends on a fundamental hero/villain contrast that also, unfortunately, becomes a racial contrast: White American Hanks vs. virtually anonymous Black African interlopers. There’s no getting around this even though the silly script by Billy Ray glosses global economy sentiments (about the Haves inevitably endangered/targeted by the Have Nots). The film’s ridiculous suggestion that American capitalism invites hostile aggression was also implicit in United 93 and explains its fatal inability to rise above mawkishness. Greengrass’s questionable political principles (he also directed the heinous anti-American thrillers Bourne Ultimatum and Green Zone) leads to the duplicitous dramatic conceit of making the Somali pirates scary yet keeping their motives vague–and stereotypical. Few critics ever notice racism in such generic form.

An early cut from Phillips’ All-American White home life to Eyl, Somalia, and its violent, caterwauling tribes recalls a Michael Winterbottom cut–a facile edit contrasting superficial cultural and political extremes. This sets up Liberal sympathy and then insidiously uses that identification to power an underlying fear of the Other. The pirates are simply dark, skinny, wild-eyed, gibbering monsters. Greengrass and Ray barely distinguish between the four who board the Maersk Alabama carrying assault weapons (except the youngest, least aggressive pirate whose “sensitivity” codes as gay, thus worthy of Liberal sympathy when he gets wounded).

It is impossible to see the pirates as anything other than marauding blacks. As physical types, they all could have been played by the actor Michael Kenneth Williams, the scar-faced actor made famous by HBO’s The Wire, singled out by President Obama as his favorite character on the series–a commendation that frees Hollywood to reproduce more hideous black stereotypes. Shaky and unconscionable politics. This scarifying zombie look (in quadruplicate) carries disproportionate impact when the Somalis are characterized without specific family worries or thoughts. At best they’re just inchoate terrorists like those Greengrass put onboard United’s Flight 93. Pretending doc realism is no excuse for this, especially when the music score brands the pirate scenes with jungle music and calm music for Hanks–except for his final crying jag.

Although the confusion of racist stereotypes may overwhelm naïve viewers, Captain Phillips is too damn obvious to be intense and the second half (set inside an orange-colored, covered lifeboat) is merely claustrophobic–what a waste of IMAX. Since Captain Phillips is unsatisfying as either documentary or drama, it merely implies a guilty connection between commercial shipping and U.S. military interests, then fails to explore or adequately contrast the economies of two distinct nations or deal with the crucial irony of American pop culture‘s violent attraction for the Third World. Captain Phillips is twisted, corrupt, lamely directed and finally, offensively simplistic.

Follow Armond White on Twitter at 3xchair