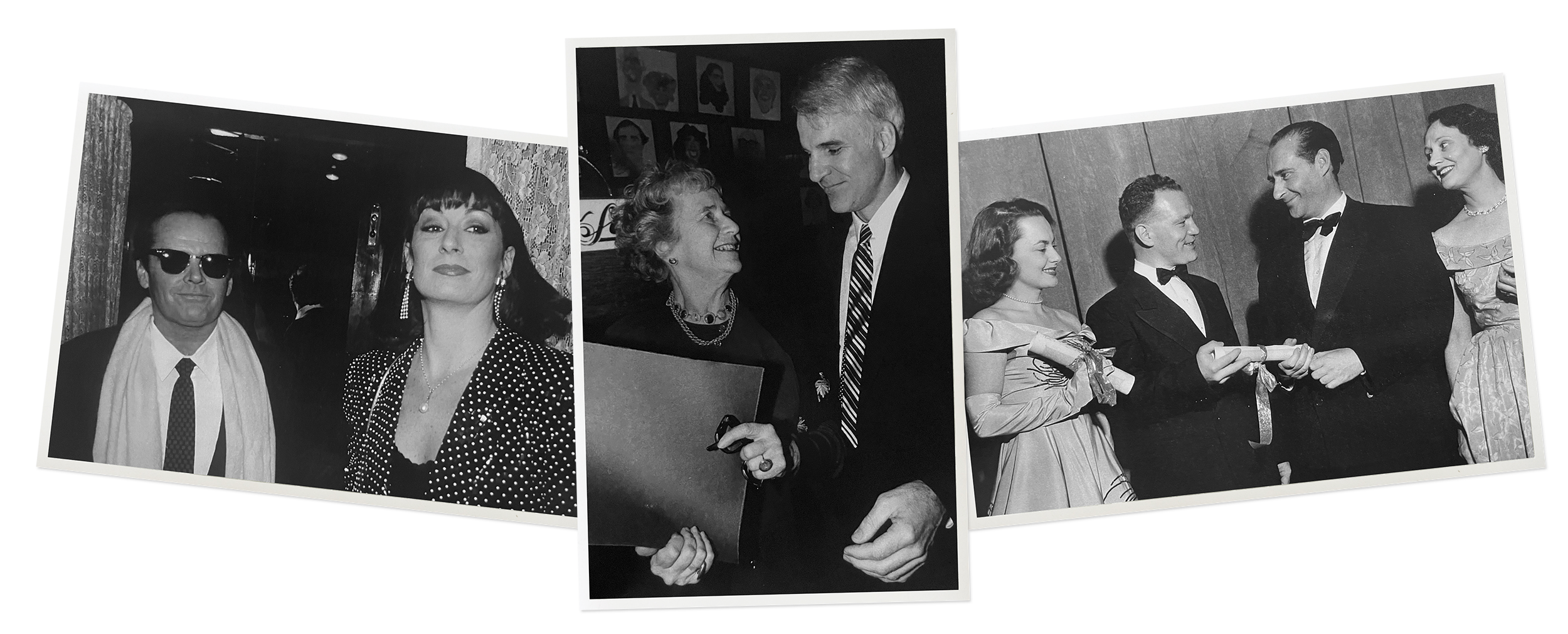

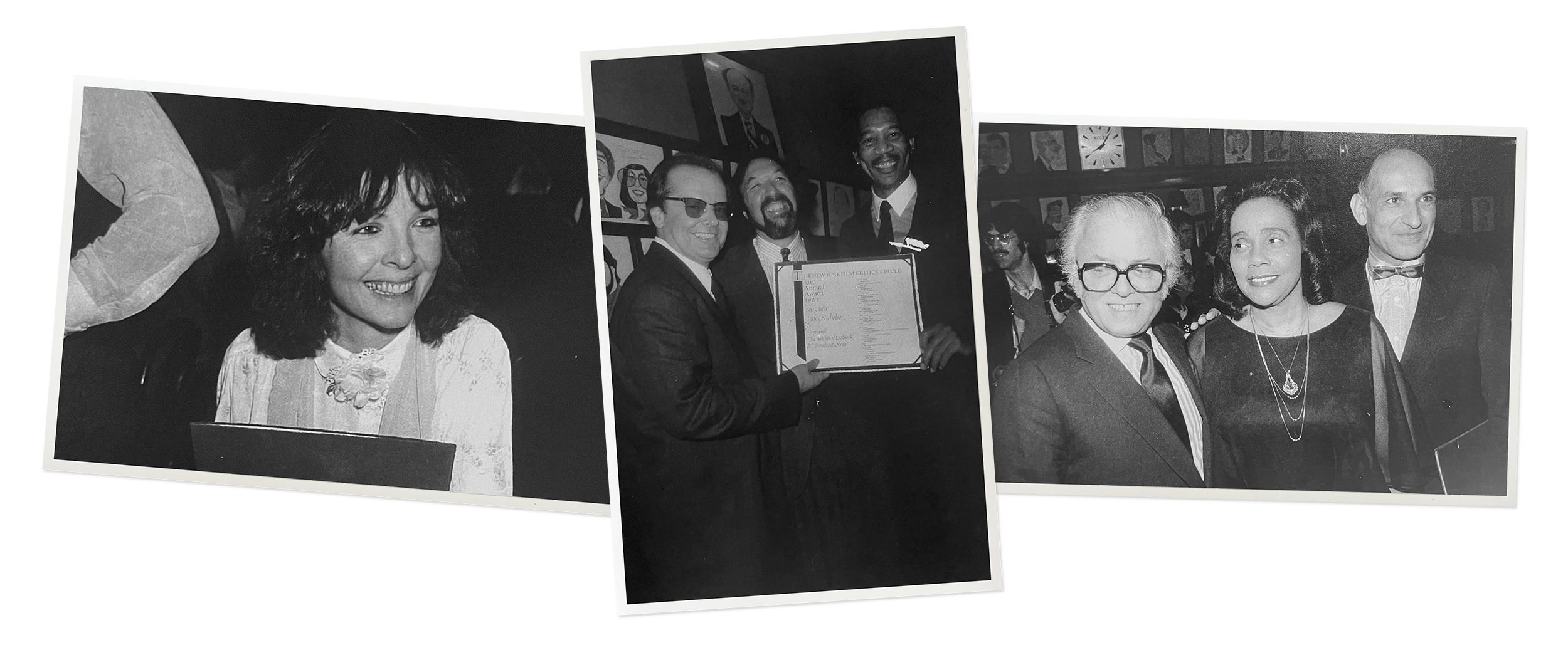

John Huston once called their award “the greatest honor that anyone in my profession can receive,” and John Ford even admitted, “it means more to me than any other honor.” For 88 years the New York Film Critics Circle has consistently recognized, championed, and defended films that may otherwise have been slighted by audiences and the entertainment industry. Founded in part as a response to the Academy Awards’s sometimes dubious selections for the annual best in cinema, the NYFCC has from the start prided itself on striving to recognize a higher standard of film.

Compared with the Oscars, the group’s best picture track record speaks for itself: Citizen Kane over How Green Was My Valley; A Clockwork Orange over The French Connection; Day for Night over The Sting; Goodfellas over Dances with Wolves. Its announcement of winners weeks in advance of the Oscar nominations even points to the group’s natural role as a prize harbinger: Since 1935, the Academy Awards have given best picture to 43% of the NYFCC’s picks.

Twenty years before the Academy Awards started doling out Oscars for best foreign film, the NYFCC was recognizing and heralding movies from other countries, including Grand Illusion, Rome, Open City, and Diabolique. The NYFCC was the first organization in the United States to celebrate The 400 Blows and fought censorship when the Catholic Church banned the 1948 omnibus Ways of Love for its inclusion of Roberto Rossellini’s sacrilegious episode The Miracle. The NYFCC even spawned another kudos-driven organization: In 1966, a few restless members like Joe Morgenstern left the group and started the National Society of Film Critics.

Traditionally, people are either invited into the group, or they apply for membership. One hundred and thirty critics have been members since the group began, among them alumni like Pauline Kael, Judith Crist, Renata Adler, and Frank Rich, who reviewed movies for Time in the 1970s; screenwriter Jay Cocks (The Age of Innocence) was even once a member. And some have shown remarkable longevity: The New York Times‘s Bosley Crowther stayed for 30 years, and seminal critic Andrew Sarris was a member for over 40.

Membership, which over the years has fluctuated from 11 to 38 people, was once strictly limited to critics published in daily New York newspapers. But the city’s newspaper strike in 1962 crippled the industry and forced the group to extend its reach to include magazines, where many of their newly-unemployed members had landed jobs. By the end of the 1960s, critics writing for national magazines like Newsweek, Playboy, The Saturday Review, and TV Guide were members. And when, in 1987, Time critic Richard Schickel moved to Los Angeles, membership broadened itself geographically, to the point where the group now enjoys three expatriates on the West Coast.

From the lively debates of the early years to today’s silent ballot, the NYFCC have always made stimulating choices every year. Strongly opinionated, passionately fervent about movies, and rarely in agreement on anything, The NYFCC has time and again remained at the crest of critical opinion in this country, leaving in its wake a rich and vibrant history. Stephen Garrett