John Carter as Wall-E Sequel

By Armond White

Andrew Stanton’ John Carter fulfills the promise of his previous film Wall-E. The dystopian state of our film culture is apparent in every luckless scene that adapts Edgar Rice Burrroughs’ 1917 adventure novel A Queenof Mars. Burroughs’ boys’ fiction had recognizable influence on more than the past quarter of pulp cinema landmarks from Star Wars and The Terminator to Attack of the Clones and Avatar.

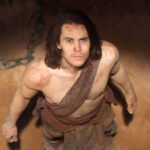

Stanton stays idiotically faithful to those films and their frivolous sincerity in telling the legend of American Civil War vet Carter (Taylor Kitsch) who’s transported to the planet Mars where he (in altered time) discovers superhuman powers–he can pogo-jump great distances like the kind Jumper and wins the admiration of the towering, spindly green Martins who resemble the blue populace of Avatar. Carter fights for the survival of the the green race and their Princess Dejah Thoris (Lynn Collins). Using the same bland color scheme as Pixar’s Wall-E, Stanton lays out the plot without a sense of wonder (at least Avatar had that). Instead, he shows a preference for bland imaginings–essentially an aversion to aesthetic narrative which has become the norm in 3D filmmaking where dark imagery and formulaic plotting go unquestioned.

Now, directing his first live-action film, animator Stanton didn’t count on the fickleness of his core audience–the geek brigade who pledge fealty to Pixar, who can only respond to Pixar–and so automatically hate on John Carter the same way their hated on Jar Jar Binks in Attack of the Clones, as if it betrayed every element of frivolity that they had enthusiastically embraced.

John Carter is easily more watchable than Wall-E and Attack of the Clones if only for its persistent human elements–Kitsch’s granitic musculature when covered in the dust of the angry red planet and Collins’ regal concentration when seriously concerned for the fate of her planet and its people. More humane direction would have made their love-match signify fundamental feelings of desire, prioritizing sensitivity over the spectacle of CGI aliens. It is impossible to feel the unique personalities,let alone faces, of Willem Dafoe, Fiona Walker, Ciaran Hinds (used so creatively in Ghost Rider: Spirit of Revenge) and Mark Strong; they’re all disguised by CGI graphics to which Stanton is more committed than the interplay of emotion. His folly justified and no doubt endorsed that the box office success of Avatar which sanctions the perpetration of F/X absurdity. Yet, John Carter and its first weekend box-office take have already been ridiculed as if Stanton had failed to live up to the expectations of adventure filmmaking (which Wall-E had already disgraced).

The lesson being taught is that contemporary film culture cannot find its way out of the rubbish to which it has become susceptible. Stanton’s live-action directing (as outlandish as the comings and goings in Thor) demonstrates his commitment to large-scale nonsense. He expands on themes of dystopia through examples borrowed form antiquity epics (John Carter’s circuitous plotting of the Martian’s own civil war) parallels America’s historical conflict to prognostication of future/contemporary moral and political issues (a brilliant strategy in Jonah Hex and classically dramatized in the quasi-Shakespearean Chronicles of Riddick). That this displeases some moviegoers proves their insensitivity to such narrative basics as plot, theme and social relevance. They prefer nonsense with the appearance of something new.

Unfortunately, the overrated Stanton lacks the visual wit that animator Brad Bird didn’t get credit for in Mission: Impossible: Ghost Protocol which maintained a human emotional scale. So John Carter is being demeaned in the marketplace as was Ghost Protocol–and The Chronicles of Riddick and Terminator Salvation and 10, 000 BC, movies that improved on sci-fi formula yet were ridiculed for trying.

When this happens, fan boy snark becomes its own self-snarking prophecy. Their tactless refusal to let Stanton grow as an artist parallels their failure to see in Wall-E what he lacks as an artist . Now they condemn him for the very hackdom he always exhibited. It’s a way fan boys (and critics) have of always making themselves feel superior; they turn their backs on filmmakers they previously praised. Call it the George Lucas Syndrome. Or call it 3D Backlash.

John Carter was always doomed to failure; coincidentally it opened the very week Bernardo Bertolucci rebuked 3D as “expensive and vulgarly commercial.” Bertolucci pinpointed the basic marketing points behind most of the recent 3-productions–warnings fan boys and critics are too credulous to heed. It would make them to face up to how adventure narrative from Burroughs to Marvel Comics gets exploited not for the beauty of revealing human experience but simply for box-office gimmicks. Dumping on John Carter is a way to avoid the fact that everything commercial Hollywood promises is also a curse.