By Armond White

In his essential book Subculture: The Meaning of Style, professor Dick Hebdige remarked that “the history of post-war British youth culture must be reinterpreted as a succession of differential responses to the black immigrant presence in Britain from the 1950s onward.” This appears to be Julian Temple’s guiding principle in London: The Modern Babylon. He unabashedly observes multicultural mixing in this revue of London’s history and its new millennial post-industrial identity.

It is primarily a youth culture observation; prioritizing Britain’s ever-changing musical codes while encompassing London’s 20th century history. Songwriter Ray Davies of The Kinks puts it succinctly when he tells Temple, “The Empire struck back with a vengeance,” describing how much the migration of colonized people into Great Britain enriched the empire city’s cultural landscape. This particular 1950s transition informs Temple’s concept. Or in Hebdige’s helpful academic terms: “Such a reassessment demands a shift of emphasis away from the normal areas of interest–the school, police media and parent culture–to what I feel to be the largely neglected dimension of race and race relations.”

It is primarily a youth culture observation; prioritizing Britain’s ever-changing musical codes while encompassing London’s 20th century history. Songwriter Ray Davies of The Kinks puts it succinctly when he tells Temple, “The Empire struck back with a vengeance,” describing how much the migration of colonized people into Great Britain enriched the empire city’s cultural landscape. This particular 1950s transition informs Temple’s concept. Or in Hebdige’s helpful academic terms: “Such a reassessment demands a shift of emphasis away from the normal areas of interest–the school, police media and parent culture–to what I feel to be the largely neglected dimension of race and race relations.”

Editing together archival footage with contemporary commentary, Temple’s cavalcade gets particularly entertaining when it almost subliminally intercuts different decades, showing the same streets and activities recurring across time: first with white Brits then Black, then Brown, then Asian, creating continuity between post-colonial social and existential experiences. “Things keep changing,” is how Suggs of the group Madness assesses it and the changing musical cues–from George Formby, Noel Coward, the Rolling Stones and the Sex Pistols to Pet Shop Boys confirms it all.

Since London: The Modern Babylon isn’t an official historical doc, it finds more peculiar details and testimonies than an institutionally sanctioned chronicler such as Ken Burns might produce. Not as deeply moving or introspective as Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City or Guy Maddin’s My Winnepeg, Temple—who in the past has been an exploitative, commercial hack–employs his own superficial yet unique and appealing view, what Hebdige might call exoticism.

Cultural exoticism can occur across a geographical distance and across time; London: The Modern Babylon’s exoticizing approach to the history of England’s capital city sets it apart from regular historical documentaries. It’s basically a pop music doc, pacing events in London’s past century to musical trends that automatically reflect it. Temple juxtaposes Benjamin Disraeli’s pronouncement “London is a modern Babylon” to Linton Kwesi Johnson’s immortal track “Inglan is a Bitch.”

This style of authentication recalls the peculiar 70s film/music hybrid called All This and World War II. But Temple, who made his name in 80s music videos then tarnished his rep with the disastrous movie musical Absolute Beginners, has found proper means for his shallow talents.

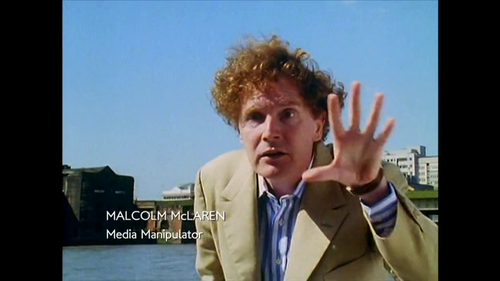

Why this harsh turn? In the film’s second half, Temple petulantly cites Malcolm McLaren as a “media manipulator” then makes an inexcusable error when patching-in a clip of Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 election victory that alters her famous speech to its negative reversal: “Where there is harmony let us bring discord, where there is hope let us bring despair.” This isn’t anarchic art but the cheap trick distorted journalism of the Gawker age. Designed as a mixed tape of images and voices, London: The Modern Babylon falls to wreckage by Temple‘s own excessive cleverness.

Follow Armond White on Twitter at 3xchair