By Armond White

By Armond White

The difference between Antonio Fargas playing a pathetic Black queen based on Jason Holliday in Next Stop Greenwich Village and Jason Holliday playing himself in Portrait of Jason is crucial. Fargas, a real actor, conveyed the multiple and paradoxical meanings in a dramatized character; Holliday, as an object of documentary curiosity is limited. His talkative, scotch-drinking, weed-smoking flamboyance may look like freewheeling audacity, but his humanity depends upon whatever a viewer will infer. In short, the legendary Portrait of Jason is not art.

The legend began with the film’s original release in 1967 (it has now been meticulously restored and revived by Milestone Films, the redoubtable distribution company). Its controversial success was bolstered by Ingmar Bergman’s famous quote “It is the most fascinating movie I have ever seen….”)–an interesting assessment also meaning a startled, unnerved, appalled reaction to Holliday holding forth an entire evening as filmmaker Shirley Clarke recorded his egotistic demonstrations.

In the late 60s this exhibition would have intrigued an outsider like Bergman as well as those wishing to safely partake in New York’s bohemian scene where White hipsters enjoyed grandstanding Black exoticism. Nothing has changed in nearly 50 years. Portrait of Jason returns to film culture at the same time films Precious and Beasts of the Southern Wild get celebrated as fetish objects of Liberal horror, pity and condescension.

Tom Wolfe coined a term for the phenomenon that Holiday represented: “Superego Negro” (from Wolfe’s famous “Radical Chic”). Hipster Clarke trained her lens on Holliday out of the same superego “fascination” experienced at one’s mirror image. Her own outsider sensibility sought explanation in Holliday’s freakshow. (Later interviews admit her vengeful motives arising from encounters with Holliday, a profligate gadabout, user, hustler, sociopath). But Portrait of Jason’s renown/infamy owes to its reception by a predominantly White, established art culture that was closed to Blacks except to see them as oddities (or drug-dealers).

Clarke’s zoo-keeper concept employs formal cinematic barriers (blurry dissolves, black leader while the tape machine keeps recording and single-shot monologue).This automatic distancing never probes Holliday’s psychology even when Clarke and off-camera friends (including black actor, scene maker Carl Lee) provoke Holliday to tell familiar, self-pitying tales. The deconstruction of 60s cinema verite style that worked so well in Clarke’s filmed-theater piece The Connection lets viewers recoil from Holliday’s degenerate egotism. Clarke confirms the fear/fascination behind Norman Mailer’s seminal essay “The White Negro.”

Even though this Walpurgisnacht was filmed in 1966, Clarke never asks about the Civil Rights Movement and urban riots which would not have just been topical, but personal. For a Black man on the margins of presumably progressive White culture and inside the gay demimonde, who changed his given name Aaron Payne, Holliday’s social awareness–or lack of consciousness–begs explication. His hustler tales defy credulity given his unprepossessing appearance, yet any sophisticated viewer must think about the unpretty but brilliant James Baldwin’s revelatory insight into the erotics of race. Without such truth, Portrait of Jason doesn’t earn the fascination it solicits.

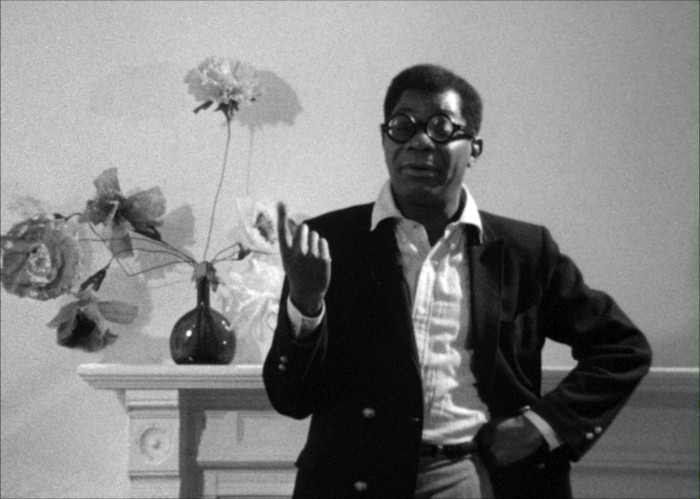

Holliday boasts “I hustle. I’m a stone whore and I’m not ashamed of it!” before eventually breaking down into teary hysterics but this gives less insight into the experience of Black social mobility than Eugene O’Neill captured in the Joe Mott monologues of The Iceman Cometh. Holiday’s self-amused, pre-Stonewall snaps (“Me, I guess I’m a male bitch because I go out of my way to unglue people”) convey gay liberation impudence. After showing his Barbra Streisand, Mae West, Pearl Bailey, Scarlett O’Hara and Dinah Washington impersonations, he also asserts “Tennessee Williams just couldn’t have done me anymore justice. Yes, I’m the bitch. Believe it. You amateur cunts, take notice. I’m the bitch!” His owl-frame eyeglasses anticipate RuPaul’s drag act but without RuPaul’s confidence–what Black and Queer studies academics call “agency.” But there can be no “agency” when the public perception of Blacks is controlled and shaped by White fears and fantasies.

Portrait of Jason revels in Holliday’s self-hatred. “I had a white boy fever. Yeah, I went through changes with those gorgeous little boys” which Antonio Fargas made poignant. But Clarke pushes him toward hysteria, taking advantage of a gay Black man’s social pathology. (Critic John Simon adroitly assessed the film “not as cinema verite (itself banal enough) but as egregious lack of cinema-charite.”) Jason appears rootless, alienated from his background, yet Clarke doesn’t assess what that means as did Terminal Bar, Stefan Nadelman’s powerful 2003 documentary about mid-20th century gay Black men who slipped into New York’s underworld. Portrait of Jason ignores that underworld by creating its own bohemian, art-movie prison. Clarke’s charity and fascinating are simply exploitation.

Follow Armond White on Twitter at 3xchair