By Armond White

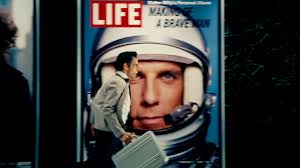

The Wolf of Wall Street and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty share the same misfortune. Both films deal with the ambition of working-class protagonists: Scorsese’s three-hour epic about a kid from The Bronx who becomes a Wall Street titan (Leonardo DiCaprio) charts his aggression through mind-altering drugs while Ben Stiller’s adaptation of the classic James Thurber story casts himself as a meek Life Magazine photography clerk searching for love and self-confidence largely through his imagination.

One film’s more interesting than the other, but neither is successful. Both represent filmmakers’ failure to clarify their own ambition or that of their subjects. Stiller’s regular spoofing (on various genres and cultural attitudes) gets needlessly inflated into a special effects extravaganza. His humor and vision are out-of proportion and misapplied (Thurber’s white-collar envy and resentment don’t easily translate to Occupy-era entitlement) so much so that he totally misses the sweet yearning and self-deprecation he had performed so well in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums.

Walter Mitty suggests a failed Wes Anderson caprice. In an effort to make his ultimate movie, Stiller’s big-budget opportunity loses the rigor necessary to capture the contradictions of the hipster generation that romanticizes its irreverence and sentimentality (Dave Eggers is their Thurber). The large scale compositions and hyperrealisitc special effects belong to a superhero comic not a working-man’s thwarted desires. (His romance with Kristen Wiig is sappy not sharp.) The milquetoast Mitty figure doesn’t speak to the era of American Idol wannabes; Stiller’s motivation is so schizoid he’s made a magnum opus mumblecore film–a debacle as unwieldy, ennervating and unfunny as the most bourgeois, overpriced Hollywood studio epics of yore.

Walter Mitty suggests a failed Wes Anderson caprice. In an effort to make his ultimate movie, Stiller’s big-budget opportunity loses the rigor necessary to capture the contradictions of the hipster generation that romanticizes its irreverence and sentimentality (Dave Eggers is their Thurber). The large scale compositions and hyperrealisitc special effects belong to a superhero comic not a working-man’s thwarted desires. (His romance with Kristen Wiig is sappy not sharp.) The milquetoast Mitty figure doesn’t speak to the era of American Idol wannabes; Stiller’s motivation is so schizoid he’s made a magnum opus mumblecore film–a debacle as unwieldy, ennervating and unfunny as the most bourgeois, overpriced Hollywood studio epics of yore.

The Wolf of Wall Street is failed Scorsese–and that’s good to the extent it avoids his usual gangster-envy. Unfortunately, he’s still working with DiCaprio which resembles the overspending, underthinking Stiller. Scorsese’s DiCaprio-era movies all lack for inspiration which means his moviemaking urge has gotten hollow and out of hand.

The first scene in The Wolf of Wall Street is of a dwarf being tossed at a wall of velcro; the first sound is DiCaprio’s still-pubescent voice as Jordan Belfort narrating his own life story. This odd-ball opening immediately marks the film as a personal expression of Scorsese’s anxieties: His is the self-sentimentalizing voice of a nerd who is dwarfed by Hollywood’s fabled system–then overwhelmed by his own reputation and advantages.

Relaying the story of Scorsese’s own success and compulsiveness, The Wolf of Wall Street gives a dreamlike account of decadent self-indulgence during his New York, New York-Hollywood years. The Wall Street setting and Belfort’s actual life story are pretext. As Pauline Kael once determined, “Scorsese is just naturally an Expressionist” and Belfort’s high-living, boastful cautionary tale becomes the parable of a reprobate (“I love drugs…and money. It makes you a better person”) who has shed the Catholic guilt of Mean Streets.

The macho excess of Scorsese’s gangster films appears as The Wolf of Wall Street’s big-budget version of Boiler Room, depicting the white ethnic “get money” subculture where Belfort meets his sidekick Donnie Azoff (Jonah Hill in a Joe Pecsi role). Their rise in the industry involves gangster-style nerve, deception and cynicism that is aided by drugs as reward and anesthesia. Belfort calls the stock market “A real wolf pit, just the way I like it.” He brags about his team’s wild European excursion: “The flight there alone was a Bacchanal.”

At certain points Scorsese’s long unvaried look at greed and self-indulgence is stupefying–Walter Mitty on steroids. With none of Mean Street’s contrition or even GoodFellas’ slight irony, this post-Oliver Stone look at Wall Street avarice turns unexpectedly, outrageously comic. Belfort’s sins of success, affluence and decadence are exaggerated and drug-enhanced–expressed in a set-piece where Scorsese (borrowing his 60s record collection) stages a dolly-in/dolly-out scan of rowdy stock-traders timed to Jimmy Castor’s raucous 1966 “Hey, Leroy, your Mama Callin’ You!”). This is prelude to a couple disproportionate scenes of Belfort’s yacht in a tempest and his domestic life with trophy wife (Margot Robbie) that climaxes with a Quaalude binge (“Cerebral Palsy stage,” Belfort says)–a bizarre, slapstick homage to Michael Powell’s Small Back Room.

At certain points Scorsese’s long unvaried look at greed and self-indulgence is stupefying–Walter Mitty on steroids. With none of Mean Street’s contrition or even GoodFellas’ slight irony, this post-Oliver Stone look at Wall Street avarice turns unexpectedly, outrageously comic. Belfort’s sins of success, affluence and decadence are exaggerated and drug-enhanced–expressed in a set-piece where Scorsese (borrowing his 60s record collection) stages a dolly-in/dolly-out scan of rowdy stock-traders timed to Jimmy Castor’s raucous 1966 “Hey, Leroy, your Mama Callin’ You!”). This is prelude to a couple disproportionate scenes of Belfort’s yacht in a tempest and his domestic life with trophy wife (Margot Robbie) that climaxes with a Quaalude binge (“Cerebral Palsy stage,” Belfort says)–a bizarre, slapstick homage to Michael Powell’s Small Back Room.

Scorsese’s comic Expressionism differs from the bombast of his other impersonal DiCaprio films yet due to a script by Terence Winter, writer of that GoodFellas knock-off The Sopranos, it’s still superficial bombast–sarcastic rather than funny–despite DiCaprio finally becoming a Marty alter-ego: the dwarf in velcro with an explosive temper. (Imagine the swagger Paul Walker could have brought to playing Belfort). Although the personal nature of this film distinguishes it, it’s still disappoints the social consciousness we once expected of Scorsese and lacks a valuable grasp of pre-Recession culture. David O. Russell’s American Hustle bests this with a closer read on vulgar aspiration.

Scorsese’s infatuation with profane behavior means The Wolf of Wall Street could easily be mistaken for another of his mobster-training films. The Expressionist auteur cheats his own confession; this is an ultra-cynical take on Walter Mitty. It celebrates Scorsese’s own recovering-addict weakness–and Belfort’s greed–as national tendencies. No wonder the panorama of faces that ends the movie repeats Jia Zhangke’s Family-of-Man condemnation in A Touch of Sin.

Follow Armond White on Twitter at 3xchair